|

|

|

|

|

The Cosmic Science of Yantra: Exploring Sacred Energy and Spiritual Harmony with Reference to Indian Neo-Tantra Artists

Dr. Sakshi Gupta 1![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Kanpur, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper investigates the cosmic

and philosophical significance of the Yantra, an ancient geometric diagram

central to Indian Tantric traditions. Combining scholarly insights from Madhu

Khanna, B. Frederics, F.W. Bunce, Philip Rowson, Lalan Prasad Sigh and Ajit

Mookerjee with an analysis of Indian Neo-Tantra artists such as S.H. Raza,

G.R. Santosh, Biren De, P.T. Reddy, O.P. Sharma, Dipak Banerjee, K.C.S. Paniker and Shobha Broota, it explores how Yantras

function as sacred maps of consciousness, instruments of ritual energy, and

modern spiritual aesthetics. Through an interdisciplinary lens encompassing

art history, metaphysics, and cultural criticism, the study reveals the

Yantra's enduring role as both visual icon and meditative technology,

bridging the esoteric past and contemporary Indian modernism. |

|||

|

Received 02 May 2025 Accepted 25 June 2025 Published 30 June 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Sakshi Gupta, gupta.sakshi2087@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/ShodhShreejan.v2.i1.2025.23 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Cosmic, Yantra, Spiritual, Indian

Neo-Tantra |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The Yantra is one of the most enduring and enigmatic forms of Indian sacred art. Emerging from the ritual and metaphysical frameworks of Tantric practice, it is typically constructed as a geometric diagram composed of triangles, circles, squares, and lotus petals that symbolically encode divine energies and cosmic principles Khanna (1994). While its primary use lies in the context of worship and meditation, the Yantra has evolved into an archetype of spiritual art, embodying both the seen and unseen dimensions of existence.

In the wake of India's post-independence search for cultural identity, a group of modernist artists turned to indigenous spiritual traditions to reinterpret abstraction not merely as aesthetic innovation but as a philosophical exploration. This shift gave rise to the Indian Neo-Tantra art movement, wherein artists such as S.H. Raza, G.R. Santosh, Biren De, and others began incorporating Tantric symbology—particularly the Yantra—into their contemporary visual vocabularies Dalmia (2001), Prasad (1983).

This research aims to trace the transformation of the Yantra from sacred diagram to modern artistic metaphor. It investigates how traditional ritual meanings, cosmological structures, and metaphysical foundations are retained, abstracted, or recontextualized in the work of Neo-Tantra artists. Drawing on foundational texts by Khanna (1994), Bunce (2001), Frederics (1998), and Mookerjee (1977), this study situates the Yantra as a living diagram—at once spiritual, aesthetic, psychological, and philosophical.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Early 18th century, Title- A JAIN SIDDHACHAKRA YANTRA, Style- Gujarat, Medium- Gouache and Gold on cloth, Size- 89.5cm x 89.5cm, Collected by Jean-Claude Ciancimino (1931-2014) in 1964 |

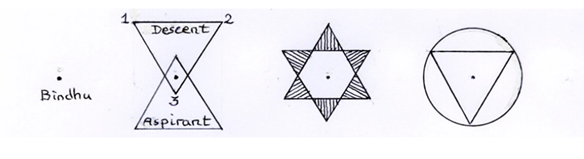

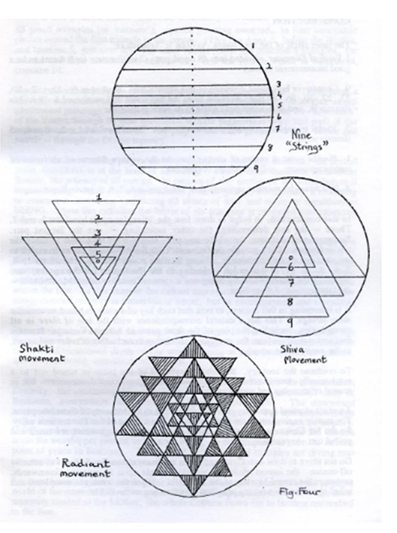

2. Sacred Geometry, Cosmology & Numerology of the Yantra

The Yantra is not merely a geometric design but a metaphysical and cosmological structure that embodies the principles of sacred geometry. According to Madhu Khanna (1994), a Yantra is “a symbolic representation of aspects of divinity, the creative forces of the universe, and the internal journey of the practitioner.” Each element within a Yantra—be it a triangle, circle, or lotus petal—corresponds to a cosmic principle. The triangle may signify energy or shakti, while the central point or bindu represents the unmanifest, the seed of potentiality.

Mookerjee (1977) further explains that the Yantra is a visualized mantra—a form of metaphysical energy transformed into a symbolic structure. He emphasizes that sacred diagrams like the Sri Yantra serve as visual metaphors for the unfolding of the cosmos, with layers of geometry representing levels of consciousness. The bindu, surrounded by interlocking triangles and lotus petals, becomes a symbolic map from the mundane to the transcendent.

Bunce (2001) adds a vital iconographic dimension, offering detailed numerological and structural analyses of deity-specific Yantras. He interprets the Sri Yantra, for example, as consisting of 43 interlocking triangles arranged in five downward-facing (female) and four upward-facing (male) formations, signifying the union of Shiva and Shakti. These structures are not decorative—they are tools of visualization and concentration. Bunce’s work provides a vital link between the physical structure and its metaphysical implications.

Frederics (1998) focuses on the ritual role of the Yantra, emphasizing that each geometric form is imbued with the shakti of a specific deity. For instance, the Kali Yantra, composed of intersecting triangles and enclosed by a circle and a square, invokes the fierce, transformative energy of the goddess Kali. This association is not metaphorical but functional—the practitioner is believed to connect with the deity through meditative engagement with the form.

This cosmological encoding is what distinguishes the Yantra from ordinary patterns. It functions as a diagrammatic microcosm, where numerical balance (such as the use of 9, 27, or 108) echoes Vedic cosmology. The repetition of forms, the precision of lines, and the symmetry all converge to form a visual field that facilitates inner transformation. The Yantra, in this context, is both a static icon and a dynamic spiritual engine.

3. Yantra as Spiritual Technology

A Yantra is not simply a symbolic form but functions as a spiritual technology—an active, energetic instrument for transformation. In Tantric practice, it is used not as an object of worship per se but as a tool to focus and align the inner vibrations of the practitioner with universal energies. Khanna (1994) emphasizes that the Yantra is a microcosmic schematic of the cosmos, and by meditating upon it, the practitioner internalizes cosmic rhythms and divine harmonies. The process is not passive contemplation; it is an immersive spiritual act.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 SYMBOLIC STRUCTURES OF THE YANTRA – From Bindu to Geometric Manifestation |

Mookerjee (1977) calls the Yantra a “dynamized diagram,” imbued with shakti through precise geometrical arrangement and the chanting of mantras. The bindu, the center of the diagram, functions as a spiritual axis—drawing in divine energy and redistributing it through the practitioner’s consciousness. In traditional ritual settings, the drawing or consecration of a Yantra is considered a sacred act equivalent to temple construction in its spiritual magnitude.

In this regard, Neo-Tantra artists are not merely creators of aesthetic compositions but facilitators of altered states of perception. Their reinterpretations of Yantras carry forward the ancient function of spiritual activation. For instance, works by S.H. Raza or Biren De, though shown in galleries and modern spaces, maintain an aura of sacredness. These compositions invite contemplative attention and performative engagement, similar to how traditional Yantras are approached during worship or meditation.

Bunce (2001) and Frederics (1998) note that the sacred geometry of the Yantra is not random; it is built upon ancient systems of proportion, mantra, and ritual activation. When contemporary artists borrow these forms, whether consciously or subconsciously, they are tapping into an ancestral repository of symbolic energy. The artist becomes a sadhaka—a practitioner using brush, color, and form as spiritual instruments.

Even when removed from temple rituals, the Yantra retains its energetic potency. Lallan Prasad (1983) points out that Neo-Tantra art represents a “spiritual engineering” wherein modern abstraction becomes a new language for cosmic alignment. Thus, these artworks are not merely secular reinterpretations but carry the potential for interior transformation—whether viewed in silence, studied for meaning, or used as meditative aids.

The Yantra in Neo-Tantra is, therefore, a living form. It becomes an energy field, a ritual object, and a contemplative device that fuses sacred intention with modern visual experimentation.

4. Philosophical and Psychological Dimensions

The Yantra operates not only as a sacred diagram or visual form but also as a deeply philosophical and psychological structure. At its core, the Yantra symbolizes the intersection of the visible and invisible, the finite and the infinite, the body and consciousness. As Mookerjee (1977) writes, the Yantra is “an ideogram of cosmic truths”—a metaphysical code that captures the flow of energy between prakriti (nature) and purusha (pure consciousness). In this sense, the Yantra is not simply an aesthetic object, but a “map” of reality drawn in geometric language.

Indian philosophical systems such as Sankhya and Vedanta are essential to understanding this structure. According to Sankhya philosophy, the universe evolves through a dynamic interaction between inert matter (prakriti) and sentient spirit (purusha). The Yantra reflects this cosmology by visually manifesting the dual forces of stillness and dynamism—usually expressed in the upward and downward triangles that signify the divine masculine and feminine energies. These energies meet at the bindu, the singular point of origin and dissolution, symbolizing the return to unity Khanna (1994).

Psychologically, the Yantra functions as an archetype—a form that Carl Jung might describe as a mandala, representing wholeness and the self. Jung (1964) considered mandalas as symbols of the process of individuation—the integration of fragmented parts of the psyche into a unified whole. In this context, the Yantra serves as a psychological instrument for self-realization, aiding the practitioner or viewer in aligning personal consciousness with universal order.

The Neo-Tantra artists participate, consciously or not, in this process of individuation. Their work becomes a terrain where inner experience, mythic memory, and spiritual longing are inscribed in form and color. Artists like G.R. Santosh or Shobha Broota use geometric abstraction to channel spiritual introspection, creating works that function both as external visual statements and internal meditative fields. These are not mere decorative patterns, but visual koans—inviting stillness, concentration, and transcendence.

As Lallan Prasad (1983) notes, the Neo-Tantra artists differ from their Western abstract counterparts by rooting their forms in spiritual and philosophical traditions. Their works engage with metaphysical thought, not in imitation but in an intuitive and experiential manner. The Yantra thus becomes a language through which philosophical depth and psychological exploration are simultaneously activated.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 STRUCTURAL DYNAMICS OF THE SRI YANTRA – Cosmic Movements and Symbolic Geometry |

The Yantra’s layered significance—philosophical, psychological, spiritual—makes it a unique instrument of inquiry and expression. In the hands of the Neo-Tantra artists, it functions not just as inherited symbolism but as a continually evolving tool for charting the self and the cosmos.

5. Neo-Tantra Movement: Historical and Aesthetic Context

The Neo-Tantra movement in Indian modern art emerged during a time of significant cultural reassessment in the post-independence period. Artists, philosophers, and critics were grappling with how to define a modern Indian identity that was not merely derivative of Western forms but deeply rooted in India's spiritual and aesthetic heritage. In this context, Tantra—with its complex symbolic systems, spiritual philosophy, and visual abstraction—offered fertile ground for a new modernist expression. The Yantra, in particular, became a key visual and metaphysical structure through which artists could negotiate tradition and innovation Dalmia (2001).

Neo-Tantra artists were not reviving Tantra in its ritualistic or esoteric form. Instead, they selectively adapted its symbolic vocabulary—primarily Yantras, mandalas, and tantric cosmograms—to forge a visual language that could communicate spiritual depth within a modern framework. As Lallan Prasad (1983) observes, this was not a literal replication of Tantric art but a “spiritual reconfiguration,” where the sacred form was reimagined through the prism of formal experimentation and subjective introspection.

The movement gained momentum in the 1960s and 70s, bolstered by key exhibitions organized by the Lalit Kala Akademi and the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA). Influential curators and scholars such as J. Swaminathan encouraged artists to look inward—to draw from India’s own metaphysical and artistic traditions rather than emulate Western modernism. This led to a rich confluence of tradition and abstraction, where artists like S.H. Raza, G.R. Santosh, Biren De, and P.T. Reddy developed distinctive styles grounded in Tantric thought and visual rhythm (Prasad, 1983).

Ajit Mookerjee’s groundbreaking publications—particularly The Tantric Way (1977)—played a pivotal role in shaping this intellectual atmosphere. His writings and curatorial work provided an accessible yet profound interpretation of Tantra, particularly its visual and ritual dimensions. Artists found in his work a justification for exploring the Yantra not only as a sacred symbol but also as a contemporary aesthetic form.

The influence of scholars like Madhu Khanna (1994) and Bunce (2001) further informed this dialogue by offering detailed iconographic and philosophical analyses of Tantric diagrams. These writings helped modern artists understand the historical, symbolic, and cosmological significance of the Yantra, allowing them to engage with it not merely as an abstract design but as a layered spiritual signifier.

Notably, the Neo-Tantra movement did not position itself in opposition to modernism but rather sought to expand its boundaries. Where Western abstraction often pursued formal purity and emotional intensity, Neo-Tantra artists imbued their works with metaphysical intentionality and philosophical depth. Their paintings were not just visual fields—they were sacred terrains, intended to guide the viewer toward inner stillness, clarity, and transcendence.

In essence, Neo-Tantra represents a unique convergence of modernist aesthetics and Indian spiritual philosophy. It demonstrates how traditional symbols like the Yantra can be reactivated in a contemporary context, offering both aesthetic pleasure and spiritual resonance. The movement continues to influence artists, designers, and thinkers who seek to balance the sacred and the secular, the modern and the timeless.

6. Artists and Their Interpretations of the Yantra

Indian Neo-Tantra artists reimagined the Yantra not merely as a spiritual icon but as a modern visual grammar capable of communicating interiority, cosmic unity, and metaphysical reflection. Each artist brought a distinct vision to the sacred geometry of the Yantra, influenced by personal beliefs, philosophical engagements, and aesthetic sensibilities. The following subsections analyze select artists whose work exemplifies this synthesis.

6.1. S.H. Raza: The Bindu as Cosmic Nucleus

Sayed Haider Raza’s engagement with the Yantra culminated in his deep exploration of the bindu—the metaphysical point of origin in Tantric cosmology. After decades of working in expressionist abstraction in Paris, Raza returned spiritually and artistically to India’s metaphysical heritage. In works such as La Terre and his Bindu series, the bindu appears as the central focus around which all other forms revolve Raza Foundation. (2014).

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Year- 2011, Title- BINDU PANCHATATTAVA, Artist- S.H. Raza, Medium- Acrylic on Canvas, Size- 120x100 cm, Exhibitions-Grosvenor Vadehra, Bindu Vistaar, London, 2012, Punlications- Grosvenor Vadehra, Bindu Vistaar, London, 2012, Published in the Exhibition Catalogue, Collection- Vadhera Art Gellery |

Raza saw the bindu not only as a geometric center but as a visual mantra—“the seed, the source of energy, the beginning of all creation” Dalmia (2001). His canvases mirror the spatial tension and meditative logic of traditional Yantras, while remaining resolutely modern in their color palette and design. His work thus transforms gallery spaces into contemplative arenas, where form and silence meet.

6.2. G.R. Santosh: Symmetry and Kashmir Shaivism

G.R. Santosh was deeply influenced by Kashmir Shaivism and its philosophical focus on the union of Shiva and Shakti. His paintings draw heavily from the Sri Yantra, employing symmetrical compositions of triangles, circles, and energy lines. His painting Shakti (1970), for example, evokes the triangular geometry of Tantric diagrams, layered with esoteric symbolism and luminous colors.

According to Khanna (1994), Santosh’s work aligns with the Sri Vidya tradition, using color and line to articulate spiritual dualities—masculine and feminine, matter and spirit, stasis and dynamism. Santosh viewed painting as a form of spiritual discipline, and his use of Tantric geometry was intended to awaken latent energies within the viewer.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Year- 1980, Title- SHRI YANTRA, Artist- G.R. SANTOSH, Medium- Acrylic on Canvas, Size- 80x60in, Collection- DAG |

6.3. Biren De: Kundalini and Energy Fields

Biren De's work stands out for its overt symbolism of the human form and its energetic awakening. Often described as the “scientist” of Neo-Tantra, De created glowing compositions with concentric circles, phallic and yonic forms, and radiating light fields that recall traditional Yantras in both form and function Mookerjee (1977).

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Year-1978, Title- AUGUST’78, Artist- Biren De, Medium- Oil on Canvas, size- 126.4x125.7cm, Collection- Peabody Essex Museum, Salem |

His painting Offering to the Unknown God (1963) suggests the upward movement of kundalini energy, with the bindu glowing like an awakened third eye. As Lallan Prasad (1983) observed, De translated Tantric visual logic into a personal language of psycho-spiritual exploration, where abstraction and eroticism merge in a sacred visual code.

6.4. P.T. Reddy: Classical Integration with Modern Form

P.T. Reddy was among the first to integrate Tantric symbolism directly into Indian modernism. His works from the 1970s Tantra Series incorporate literal depictions of Yantras and Tantric figures against abstract backgrounds. He combined traditional symbolism with the modernist principles of color fields and spatial abstraction (Prasad, 1983).

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Year- 1985, Title- CONCEPT OF SUN, Artist- P.T. Reddy, Meduim- Acrylic and sketch pen on canvas Size- 11.7 x 121.9 cm. Collection- Southbey’s |

Frederics (1998) credits Reddy with pioneering a form of visual collage that retains the sacred integrity of the Yantra while making it intelligible to modern audiences. His use of layered textures and balanced geometry makes his work a visual bridge between classical metaphysics and experimental aesthetics.

6.5. K.C.S. Paniker: Glyphic Abstraction and Sacred Texts

K.C.S. Paniker’s Words and Symbols series (1965–75) takes a linguistic turn, transforming the Yantra into a semantic and visual code. Paniker filled his canvases with invented scripts, symbols, and sacred references that mimic the effect of Tantric diagrams. Rather than using precise geometric forms, he evoked the Yantra's meditative quality through pattern, color, and spatial rhythm.

His paintings function as sacred palimpsests—inviting interpretation, decoding, and spiritual introspection. Mookerjee (1977) places Paniker’s work within the broader context of symbolic abstraction, where text, symbol, and visual mantra coalesce into a sacred language of the self.

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Year- 1968, Title- WORDS AND SYMBOLS SERIES, Artist- K.C.S. Paniker, Medium- Oil on Canvas, Size- 61x74.9cm, Collection- Pundole’s |

6.6. Shobha Broota: Silence, Minimalism, and Meditative Surfaces

Shobha Broota’s work diverges from the overt geometry of other Neo-Tantra artists but remains deeply rooted in yantric thought. Her minimal, textured canvases—often in shades of white, beige, or soft pastels—resemble the repetition and silence of meditative chanting. In works like Soundless Chants (1998), the sacred is not asserted but implied, emerging through tactile resonance and spatial harmony Broota (2020).

Broota’s emphasis on “soundless energy” aligns with the Yantra’s purpose as a silent container of shakti. Her use of fiber, thread, and textured pigment introduces a feminine dimension to the largely male-dominated Neo-Tantra aesthetic, echoing the soft geometry and inward focus of the Sri Yantra’s lotus petals.

Broota’s works can be interpreted as visual equivalents of Tantric inner stillness, where form dissolves into vibration. Rather than employing explicit yantric diagrams, she invites the viewer into a contemplative state through material subtlety and rhythmic repetition, reflecting the essence of pratyāhāra (withdrawal of the senses) in Tantric practice. Her quiet surfaces are not empty; they are fields of latent energy, where the act of perception becomes meditative engagement. As Khanna (1994) notes, true yantric energy need not always reside in geometry—it can manifest through intuitive abstraction, invoking the same spiritual resonance. Broota’s practice thus broadens the Neo-Tantra vocabulary, offering an embodied, feminine, and deeply experiential vision of the sacred.

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Year- 2005, Title- RESONANCE, Artist- Shobha Broota, Medium- Oil on Canvas, Size-60x60inch |

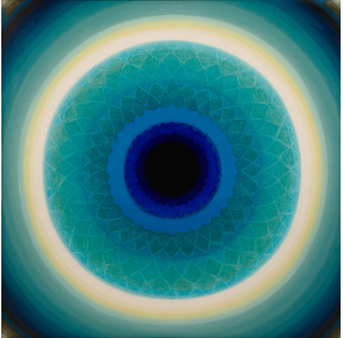

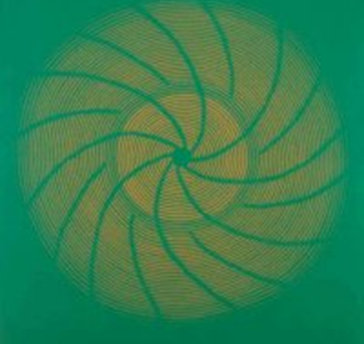

6.7. O.P. Sharma: Sacred Light and Optical Vibrations

O.P. Sharma approaches the Yantra as a vehicle of sacred light and energy. Trained in both Indian traditions and Western modernism, Sharma’s paintings like Cosmic Rhythm (1980s) feature luminous spirals, mandalas, and glowing orbs that reflect the Yantra’s energetic principles Sharma, O. P. (2016). His works are not schematic Yantras but perceptual fields—visual meditations on cosmic order and rhythmic balance.

Frederics (1998) notes that Sharma’s contribution lies in merging optical dynamics with metaphysical inquiry. His use of light and geometric fields transforms the canvas into a vibratory diagram—a space of experiential contemplation.

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Year- 2018, Title- INTERLUDE, Artist- O.P. Sharma Medium- Oil on canvas, Size- 85 x 70 cm Collection-STORYLTD |

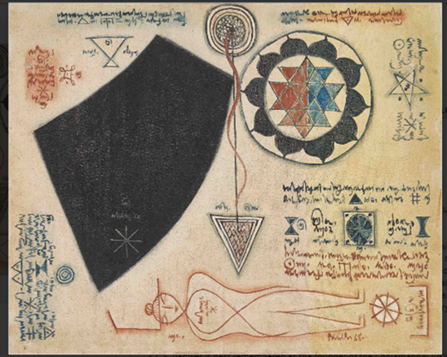

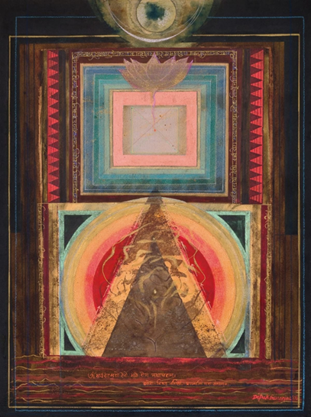

6.8. Dipak Banerjee: Symbolic Landscapes and Sacred Geometry

Banerjee (1936–2020) is a key Neo-Tantra figure whose art transforms tantric ideas into subtly symbolic visual narratives. Rather than using traditional Yantra diagrams, he employs elemental icons—suns, serpents, eyes, triangles—layered in compositions that evoke inner cosmological journeys Khanna (1994). His series such as Panchabhoota reflect cycles of creation and dissolution through elemental integration, a motif also evident in depicted works like Jagan Mata and Devi.

Art historian Dipak Ananth describes Banerjee’s output as “spatial meditations” that merge symbolic abstraction with experiential stillness Ananth (1997). Ajit Mookerjee situates this approach within Tantra’s broader “visionary mode,” in which spiritual experience supersedes literal iconography Mookerjee (1977). By weaving tantric motifs into geometric and symbolic fields, Banerjee crafts a visual language both personal and transcendent—mirroring the transformative spirit of Yantra without replicating its form.

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Year- 2008, Title- JAGAN MATA, Artist- Dipak Banerjee Medium-Mixed Media on Canvas, Size- 29x21in, Collection- Sanchit Art |

7. Comparative Synthesis of Artistic Approaches

While all Neo-Tantra artists discussed share a commitment to exploring the spiritual and symbolic dimensions of the Yantra, their interpretations reveal a diverse range of aesthetic strategies, metaphysical concerns, and visual vocabularies. This comparative synthesis aims to highlight both their commonalities and distinctive contributions.

At the core of each artist's work is the attempt to bridge ancient metaphysical structures with contemporary artistic practice. For example, S.H. Raza’s focus on the bindu emphasizes the ontological unity and cosmic stillness inherent in Tantric metaphysics Dalmia (2001), whereas G.R. Santosh employs symmetry and color to visualize the dynamic union of masculine and feminine energies within the Sri Yantra structure Khanna (1994).

Biren De and P.T. Reddy approach the Yantra more energetically—De through concentric vibrations symbolizing kundalini, and Reddy through direct collage of tantric iconography. Their canvases function as energetic fields, designed to elicit not just reflection but internal awakening Mookerjee (1977), Prasad (1983).

In contrast, artists like K.C.S. Paniker and Shobha Broota engage the Yantra as a silent, textual, or tactile presence. Paniker replaces diagrammatic form with symbolic script, creating visual texts that evoke the decoding function of the Yantra, while Broota uses material and repetition to manifest contemplative silence. These gestures parallel the Yantra’s meditative function—though abstracted into personal language Broota (2020).

O.P. Sharma, meanwhile, represents the sensorial frontier of the movement. His luminous geometries translate yantric ideals into optical experiences, aligning with the Yantra’s deeper role as a visual technology for consciousness transformation Frederics (1998).

Despite these differences, a few key threads bind their approaches:

· Sacred Geometry as Language: All these artists treat geometry not as formal abstraction but as a metaphysical grammar capable of conveying spiritual truths.

· Inner Vision Over Outer Description: Neo-Tantra painting shifts the focus from narrative content to inner vision, reflecting the meditative ethos of the Yantra.

· Modernity Infused with Tradition: The movement is not a revival of ritual Tantra but a re-engagement with its symbols and energies within modernist frameworks.

Together, these artists demonstrate that the Yantra is not a static relic but a living, adaptive structure—capable of expressing both individual insight and cosmic order in equal measure. In their hands, it becomes a spiritualized form of modernism—responsive to both cultural continuity and creative innovation.

8. Contemporary Relevance: From Ritual to Aesthetic Hybrid

In the 21st century, the Yantra has transcended its traditional ritual boundaries to emerge as a potent symbol in global aesthetics, design, spiritual philosophy, and contemporary art. This renewed relevance speaks not only to its visual power but to its capacity to embody balance, transcendence, and harmony in a fragmented, fast-paced world.

As Frederics (1998) and Bunce (2001) observe, the Yantra is an archetype of universal order—its symmetrical structure and encoded symbolism function as maps of both the cosmos and consciousness. In today’s context, where attention is divided and spiritual grounding often lost, the Yantra offers a counter-narrative: stillness over speed, interiority over spectacle, sacred pattern over chaotic noise.

Khanna (1994)emphasizes the Yantra’s role as a "sacred interface," where ancient metaphysics meets meditative functionality. In modern design cultures, the Yantra is now referenced in everything from architecture to virtual reality environments, yoga studios to augmented reality meditation apps. Its mathematical clarity and spiritual heritage have enabled it to serve as a cultural bridge between science and mysticism, East and West, past and future.

Neo-Tantra artists, by secularizing and modernizing these symbols, laid the foundation for this contemporary engagement. S.H. Raza’s Bindu series, for instance, continues to be exhibited worldwide not merely as abstract art but as spiritual philosophy in visual form. Shobha Broota’s minimalist canvases and O.P. Sharma’s luminous fields are now included in exhibitions addressing art and healing, visual consciousness, and spiritual ecology.

At the same time, this evolution raises questions about authenticity, cultural appropriation, and commodification. The transformation of the Yantra into design motifs or digital effects may dilute its symbolic intensity. Lallan Prasad (1983) warned against reducing sacred diagrams to decorative modernism without acknowledging their metaphysical depth.

Nonetheless, the Yantra’s adaptive capacity is also its strength. Its essence lies in facilitating darshan—a sacred vision or encounter with the divine. Whether in temple rituals or gallery installations, printed on cloth or animated in pixels, the Yantra retains its power to focus, transform, and inspire.

As spiritual aesthetics evolve in the digital age, the Yantra continues to offer a visual language for sacred experience—timeless yet timely, anchored in tradition yet endlessly renewed through creative innovation.

9. Conclusion

The Yantra, in its essence, is more than a sacred diagram; it is a cosmological map, a psychological mirror, and an artistic matrix. Rooted in the spiritual and metaphysical traditions of Tantra, it has evolved into a dynamic visual form that transcends temporal and cultural boundaries. Through the Neo-Tantra art movement, artists such as S.H. Raza, G.R. Santosh, Biren De, P.T. Reddy, K.C.S. Paniker, Shobha Broota, and O.P. Sharma have reinterpreted this ancient symbol to reflect both personal spirituality and collective metaphysical inquiry.

Their works do not merely illustrate the Yantra; they embody it. The Yantra becomes not only a symbol but a method—of painting, perceiving, and ultimately transforming. These artists use its structure to convey philosophical concepts from Sankhya and Vedanta, psychological dimensions akin to Jungian mandalas, and sacred energies embedded in ancient ritual practices. The integration of insights from scholars such as Madhu Khanna, Ajit Mookerjee, B. Frederics, F.W. Bunce, and Lallan Prasad further deepens the contextual understanding of the Yantra as a vibrant, multilayered symbol.

Today, in an increasingly secular and digitized world, the resurgence of interest in the Yantra—in art, mindfulness practices, and visual culture—signals a broader search for coherence, focus, and inner balance. The Neo-Tantra movement has played a crucial role in this transformation, not by merely reviving Tantric forms but by reshaping them to suit contemporary spiritual sensibilities.

Ultimately, the Yantra remains a living testament to the possibility of sacred modernism—a fusion of ancient wisdom and avant-garde creativity, geometry and divinity, silence and vibration. It continues to invite viewers not just to look, but to contemplate; not merely to analyze, but to align—with the cosmic, the internal, and the infinite.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Adams, J. (2012). How to draw the Sri Chakra Yantra. Jane Adams Art.

Ananth, D. (1997). Re-imagining the Sacred: Deepak Banerjee and

the language of the

inner. Art Heritage Review.

Broota, S. (2020). Personal

Interview Published in Lalit Kala Contemporary

Journal.

Bunce, F. W. (2001). Yantras of Deities and their Numerological foundations: An Iconographic Consideration. D.K. Printworld.

DAG. (n.d.). Awakening: A retrospective of G. R. Santosh. DAG World.

Dalmia, Y. (2001). The making

of Mdern Indian art: The Progressives. Oxford University

Press.

Frederics, B. (1998). Yantra:

The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic

Unity. Thames & Hudson.

Grosvenor Gallery. (2011). Sayed Haider Raza: Bindu Panchatatva.

Guha-Thakurta,

T. (1992). The Making of

a New Indian Art: Artists, Aesthetics and Nationalism in Bengal, c.1850–1920. Cambridge University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his Symbols.

Dell Publishing.

Khanna, M. (1994). Yantra: The Tantric

Symbol of Cosmic Unity.

Thames & Hudson.

Khanna, M. (2003). The tantric way: Art, Science, Ritual. Inner Traditions.

Krishnan, A. (2010). Contemporary Indian art and the Neo-Tantric Movement. Marg Publications.

Lyon & Turnbull. (2025). A Jain Siddhachakra Yantra, India, Gujarat or Rajasthan, 18th/19th century [Lot 108, Islamic & Indian Art Auction]. Lyon & Turnbull.

MAP Academy. (n.d.). Working with tradition: Forms and philosophies.

Mookerjee, A. (1977). The Tantric Way: Art, Science, Ritual. Thames & Hudson.

Mookerjee, A. (1982). Kundalini: The Arousal of the Inner Energy. Destiny Books.

Panikkar, R. (1993). The Vedic Experience: Mantramañjari. Motilal Banarsidass.

Pundole’s. (n.d.). Words and Symbols Series [Auction lot].

Raza Foundation. (2014). S.H. Raza: Bindu, Space

and Time [Exhibition catalog].

Sanchit Art. (n.d.). Dipak Banerjee.

Sharma, O. P. (2016). Personal Interview, National Gallery of Modern Art Archives.

Singh, K. (2015). A Visual History of Indian

Modern Art: The Sacred &

the Sensual (Neo-Tantra erotic art) (9) 1652). Delhi Art Gallery.

Singh, L. P. (1983). Neo-Tantra: Modern

Indian art and the Sacred.

Lalit Kala Akademi.

Singh, L. P. (2010). Tantra: Its Mystic and Scientific Basis. Concept Publishing Co.

Sotheby’s. (2020). Pakhal Tirumal Reddy: Concept of Sun [Lot 9, Modern & Contemporary South Asian Art Auction].

StoryLTD. (2024). Om Prakash Sharma – Interlude [Lot 14, Charity Auction]. https://www.storyltd.com/auction/item.aspx?eid=4795&lotno=14

Zimmer, H. (1955). The art of Indian Asia: Its Mythology and Transformations (Vols. 1 & 2). Princeton University Press.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhShreejan 2025. All Rights Reserved.