|

|

|

|

|

Matches are made in heaven: Traditional modernity on Over-the-Top Television in India

Mona Das 1![]()

1 Satyawati College (Day), University of Delhi, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This study examines the evolution of

television in India, focusing on the transition from traditional TV to

over-the-top (OTT) platforms. It explores how OTT content, particularly the

Netflix series "Indian Matchmaking," balances traditional values

with modern sensibilities. The research traces the development of Indian

television from state monopoly to digital revolution, analyzing its impact on

societal norms and cultural values. The study highlights the growing

influence of OTT platforms in shaping viewer preferences and cultural

narratives, especially among young urban audiences. It discusses the economic

implications of this shift and its effects on content creation and

consumption patterns. The paper also delves into the representation of

marriage and family themes in "Indian Matchmaking," examining how

the show navigates traditional practices within a contemporary global

context. The research concludes by reflecting on the broader societal impact

of OTT platforms and their role in shaping cultural identity in an

increasingly digital India. |

|||

|

Received 08 September 2025 Accepted 14 October 2025 Published 08 November 2025 Corresponding Author Mona Das,

monadas@satyawati.du.ac.in

DOI 10.29121/ShodhShreejan.v2.i2.2025.38 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Over-The-Top (OTT)

Television, Cultural Narratives, Traditional Practices, Indian Matchmaking,

Netflix |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The digitalisation of television in India, like all other phases of its historical development, has unleashed unique social and cultural processes. Research has demonstrated that television can significantly influence attitudes and behaviours by disseminating information and providing exposure to certain topics. A substantial body of literature examines the evolving trends in television viewing.

Since its inception, the television has been instrumental in shaping Indian society. Initially, it served as the primary medium through which viewers, particularly in rural areas, gained access to information about the world beyond their immediate environment. The cable era of the 1990s and the 2000s signalled women’s entertainment as the primary domain of television programming, with changing gender norms becoming a focal point in studies. The phenomenon of 'TV everywhere' or OTT in India commenced around 2010, experiencing significant transformations post-2016 with the advent of global platforms such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video. Urban audiences disillusioned with the content of traditional television have flocked to OTT platforms in search of a meaningful viewing experience. This study focuses on enduring societal values that are transformed into contemporary forms through over-the-top (OTT) platforms. Specifically, this study examines matchmaking and marriage as traditional activities deeply embedded in societal values, which, when depicted on OTT platforms, attempt to balance modernity, market dynamics, and tradition.

If television of the 90's represented an era of regressive soap operas based on joint family dramas, OTT marks ‘global’ content revolving around family and its values as the mainstay of viewership. This paper is based on the OTT series ‘Indian Matchmaking’. This study attempts to investigate the ‘continual process of deconstruction and construction’ of the meaning of family and its values over time.

‘Indian Matchmaking’, streamed on Netflix, ran for three seasons. It is a docuseries in which a renowned matchmaker from Mumbai tries to find partners for her clients based in India, the USA, and Europe, offering an inside look at an archaic custom in the modern era. It revolves around the idea that tradition can find love where modernity fails. This paper analyzes the symbols and meanings emerging from this series. The audience reception of both series is an indicator of the ensuing cultural processes.

This paper is divided into three sections. The first section recounts a brief history of television in India, focusing on the values transmitted and their societal impact. This section delves into the existing literature on television as mass media in India from the 1960s to its digital version as OTT. The second section maps the ever-growing footprint of the TV industry and its market share, particularly in contemporary times. This section contextualises the impact indicated by the preceding section. It seeks to answer why TV and its content matter in Indian society. The third section analyzes the content of the OTT series under study, ‘Indian Matchmaking’.

2. Television in India: State Monopoly to Digital Revolution

Television was introduced in India in 1959 on an experimental basis in Delhi. It picked up pace only in 1975 with for several decades. No more than 600,000 TV sets were sold until 1977. It was state-owned and heavily regulated with limited programming telecast at set hours. In 1982, however, the state-run broadcaster Doordarshan introduced colour television, which significantly boosted both interest in and viewership of television. Despite this, most programming continues to focus on government-sponsored news or information related to economic development. There were a few entertainment serials telecast weekly and watched intently. The first few decades of state-monopoly television saw TV as an extension of the developmental state. Doordarshan was the official telecaster of carefully calibrated information and knowledge generated through capillaries of power.

The early 1990s witnessed the ‘cable revolution’, a breaking-out of the governmental tentacles. Non-governmental programming was accessed via satellite signals captured by a dish antenna. The network of cables connected individual TV homes nearby to the signal receiving centre. Small entrepreneurs were instrumental in running these networks for a fee. CNN and STAR TV were the initiators of this revolutionised televiewing. The opening up of the telecast network signalled several turnarounds, primarily the duration and content of the telecast. TVs role of TV metamorphosed from a ‘teacher-informer’ to ‘entertainer’ Mehta (2008).

Between 2001 and 2006, around 30 million households, which equates to roughly 150 million people, subscribed to cable services National Readership Studies Council. (2006).

Daily soap operas have become the central plank of entertainment. To expand viewership, measured as TRP, long-format soap operas centred around an ideal, sacrificing female protagonist were promoted. The market moved with an understanding that housewives were ‘committed’ consumers of television given their ‘free’ time Deori et al. (2021). Webster and Lichty (1991) concluded that housewives in the sub-continent could devote time to watch programs both in terms of frequency and duration. They also showed a greater propensity for group viewing and attention.

The content was created with these considerations in mind. Sindoor, mangalsutra, gaudy sarees, rich-upmarket yet traditional families celebrating festivals became the hallmark of these teleserials. One of its iconic series, Kyonki Saas bhi Kabhi Bahu Thee, which has been recently brought back in its second season after a quarter of a century, symbolically depicted the challenges faced by ‘every’ Indian household. The actual or the families of aspirations that these serials represented made them as popular or more popular than tele creations of mythological dramas of the late 80s. At times, satellite TV networks adapted ‘hit’ overseas formats to Indian tastes, with Star Plus being particularly disposed towards such adaptations. However, when it came to original production, the format was set, with family drama as the staple. These soap operas marked with conservative value systems were like anchors in an alienating, liberalised social economy. The soap operas of the 1990s running into the 2000s came in for severe criticism for their portrayal of women and their familial roles. However, studies such as Jensen and Oster (2009) conducted in five Indian states between 2001 and 2003 underline the positive impacts of cable television on the lives of rural women. They note, with significant caveats, that the introduction of cable television reduced the acceptability of wife beating and son preference and increased female school enrolment as well as women’s autonomy in physical movement. Sohini Ghosh points to the complexity underlying viewers experience of seemingly retrogressive TV soaps. She notes that serials ‘allow for the playing out of very real conflicts in a rapidly globalising India. Extra-marital affairs, surrogate motherhood, non-monogamy, and a variety of erotic tensions. These transgressive ideas can be engaged with precisely because the soaps work on many registers- the most overt being seemingly conventional’ Raj (2008). The revolution that began in the 1990s peaked in the 2000s. Between 2001 and 2006, approximately 30 million households subscribed to cable services National Readership Studies Council. (2006). This rapid growth in cable subscriptions set the stage for the next evolution in India's media landscape. The ‘cable boom’ was accompanied by an intensely competitive market of channels trying to cash in on it. However, massive pilferage of cable subscription revenues because of a highly decentralised market forced channels to depend on advertising revenues to run shops. Uday Shankar the CEO of Star TV pointed to a ‘deepening crisis of content’ on account of the structural economy of TV which forced channels to focus on content with the lowest common denominator Mehta (2015). TV was unprofitable, and the ‘crisis of content’ left audiences unentertained. Recognising changing consumer preferences and technological advancements, media companies began exploring alternative content delivery methods.

In 2008, Reliance Entertainment launched India's first independent OTT platform, BIGFLIX. Two years later, in 2010, Digivive introduced nexGTv, India’s first OTT mobile app, which offered both live TV and on-demand content. nexGTv was a trailblazer in live-streaming Indian Premier League matches on smartphones in 2013 and 2014. The acquisition of IPL streaming rights in 2015 played a crucial role in the rise of another OTT platform, Hotstar (now JioHotstar), in India. The momentum for OTT platforms in India gained further traction with the launch of DittoTV (Zee) and SonyLIV around 2013. The Indian OTT landscape underwent rapid transformation with the entry of global giants such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video in 2016. There was a discernible movement towards OTT, intensifying competition for traditional TV. The lockdowns during the CoVID-19 pandemic hastened this trend. This led to a rise in viewership and expenditure on OTT platforms as people had more time to consume digital content from home Madnani et al. (2020).

The advent of over-the-top (OTT) television has dramatically reshaped media consumption. This trend is particularly evident among young viewers. Content diversity, cost efficiency, and technological integration are significant factors that make OTT more attractive than traditional Pay TV services. The flexibility and interactivity of OTT services, exemplified by features such as binge-watching and easier content navigation, have increased their appeal, resulting in higher subscription rates and continued user engagement Menon (2022), Chang and Chang 2020). OTT is reported to deliver high satisfaction, particularly on metrics such as convenience and relaxation Puthiyakath and Goswami (2021). India's over-the-top (OTT) market exemplifies a dynamic transformation in media consumption patterns, characterised by heightened user engagement and a growing preference for digital streaming platforms over traditional television. OTTs have a cumulative subscription base of 70 million, with an ever-growing potential market. The key to this market expansion was identified as price and content.

Digitalisation has democratised access to content, with smartphones emerging as the dominant screen. The proliferation of digital technologies, particularly smartphones, has fundamentally transformed the content consumption and distribution landscape. This shift has given rise to 'roaming audiences,' who can access a vast array of content anytime, anywhere. The ubiquity of smartphones as the primary screen for content consumption has not only altered viewing habits but also profoundly impacted how individuals construct their identities, perceive their nation, and develop a sense of self. This democratization of content access has blurred geographical boundaries, exposed users to diverse cultural perspectives, and created new forms of digital communities. These roaming audiences have ramifications for identity formation, nationhood, and the self. Before delving into the consequences of OTT, it is crucial to frame its development within the context of its economic growth as an industry, as this greatly affects its social influence. This study focuses on mapping societal footprints, specifically examining how traditional and modern elements are represented and blended in the context of marriage and family themes.

3. The ‘sunrise’ sector

India's media and entertainment (M&E) industry is classified as a ‘sunrise’ sector due to its rapid expansion. It has reported exceptionally high growth with an ever-increasing average revenue per user (ARPU).

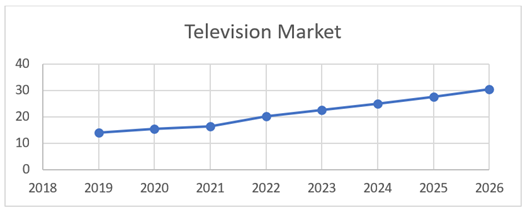

By 2016, India had emerged as the second largest TV market in the world, with over 160 million TV households. TV penetration rose to 69 percent by 2020, with remarkable extension into semi-urban and rural areas. It was reported that 109 out of 197 TV sets were located in rural areas (data source) [insert reference]. The market for television sets is projected to register a growth of 52 percent in four years, from 20 million units sold in 2022 to 30.4 million units in 2026 (Fig 1). This is because the TV-set itself has been rendered marginal for accessing content, with phones, tablets, and other mobile devices occupying centre-stage.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Source Statista |

This rapid expansion can be attributed to the sector’s unique capacity to innovate and keep pace with technological advancements and shifts in consumer preferences. The latest growth trends have been enabled by multiple factors, including the availability of fast, affordable Internet, rising incomes, and expanding consumer durable purchases.

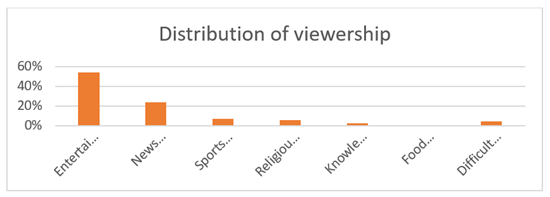

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Source Statista |

If one analyzes the distribution of viewership, it is clear that entertainment channels have captured a large share of viewers. Hence, it is clear that most people switch on their TV sets for entertainment. The emergence of over-the-top (OTT) platforms has brought about rapid changes in what content is accepted as meaningful entertainment. OTT has disrupted traditional media ecosystems, challenged established business models, and reshaped audience expectations. The economic implications of OTT growth are significant, with the industry experiencing rapid expansion and attracting substantial investment. This economic context is essential for understanding the broader societal impact of OTT platforms, as their financial success has enabled them to invest in diverse and high-quality content that further fuels their adoption and influence on global culture.

OTT platforms are gaining traction, particularly among millennials. Users do not have the patience to watch programmes in a linear model. The content-on-demand style has emerged as a popular alternative Gomathi ant Christy (2021). Punathambekar and Kumar note the ‘inter-medial and multi-scalar’ dimensions of TV in South Asia (2014). Rangaswami’s study reveals that young people in urban slums have turned their phones into 'instances of consuming culture'. There is an urge to connect with those of a higher social rank to pursue the ambition of climbing the social ladder. This connection could be ‘real’ as on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or in fantasy by consuming ‘fairy-tales’ of the OTT Rangaswami (2015).

In certain senses, OTT has emerged as a cultural medium to convey a diverse array of ideas, ideals, ideologies, images, and imaginations across different times and spaces, reflecting the collective imaginations of its audiences Punathambekar and Kumar (2014). We will analyse some of these collective imaginations, particularly those related to marriage.

4. Indian Matchmaking

Indian Matchmaking is a reality TV show produced by Smriti Mundhra that premiered on Netflix in July 2020. It has registered a place in Netflix’s top 10 series. The show received approval for a second and third season, which were streamed in August 2022 and April 2023, respectively. Mundhra, an American director and producer of Indian origin, has been engaged with Hollywood for over two decades and has taken up issues of social justice affecting American society with a focus on the South Asian diaspora. Her body of work attests to this cinematic concern–A Suitable Girl’ and ‘St. Louis Superman’ being cases in point.

Indian Matchmaking was Mundhra’s second venture on the theme of marriage. For South Asians, marriage is a pivotal moment closely tied to communal identity. Indian Americans, often regarded as a model minority with successful careers, attribute much of their success to the strong family bonds fostered by enduring marriages. These marriages are perceived as a solid foundation for their academic and professional accomplishments. However, traditional/arranged marriages and the entire process of getting married is a bit of an enigma for young desis born and brought up in America or other parts of the world. They are most often torn between appreciation for their parents ‘happily ever after’ lives and condescension for quirky Indian customs. In the documentary ‘A Suitable Girl’ (2017), streamed on Netflix, Mundhra explores arranged marriages from the perspective of three Indian girls of ‘marriageable’ age and their parents. In some senses, the theme was a lived experience for Mundhra, and she wanted to turn the spotlight on it. The film featured Sima Taparia, a matchmaker from Mumbai, as the mother of one of the subjects.

Mundhra found Sima Taparia, the matchmaker, an amazing character in her own right ‘who deserved a platform through which the mechanics of the service industry around matchmaking could be explored creatively. Her ‘straightforward worldview’ and ‘horrifyingly blunt’ attitude made her ‘disarmingly charming’ as a screen subject. The marriage industrial complex built around getting people married, of which Sima Taparia is an important player, fascinated the Indian-origin American filmmaker.

The matchmaking process on the show begins with Taparia visiting the homes of her clients in different cities in the USA, UK, and India. She literally inspects closets, kitchens, and rooms to assess the family’s means. The camera pans through the beautiful homes of lawyers, doctors, teachers, and business people–all very successful professionally but without partners. The glitzy lives and shiny homes appear sad because the daughter or son, most often in their late 30s, is unable to find a ‘match’. The upper-middle class of the diaspora, rich Indian business boys, and ‘self-made’ girls all admit to having tried dating apps and matrimonial sites before going to Sima ‘aunty’. Sima aunty invariably assures them and their families that everything will be alright now that she has arrived. In the introductory discussion, she asks the clients and their families for their ‘criteria’ of a suitable match which is invariably peppered by Sima’s pet line: ‘you will not get hundred percent, if sixty to seventy percent is there you should meet’. All parents agree with Sima, at times recounting their own experiences of meeting their life partners for no more than 30 minutes before getting married. Taparia shares her own arranged marriage story, aimed at attesting that one should not make a big deal about compatibility, getting to know each other, etc. She underlines that marriage is a compromise.

Drawing on the preferences of individuals, their parents, and her extensive years of matchmaking experience, she suggests prospective partners. She asks her clients to choose one out of two or three biodatas dug out by her. The client is made aware of her linear process of fixing meetings, as she categorically states that giving more than one option will get the client ‘confused’. Sima Taparia has her own assessment of clients spoken out loud on camera. Independent, successful women, in particular, are often denigrated as being very stubborn, egoistic, choosy, and confused. Sima aunty, like all ‘aunties, seems desperate to forge alliances, and the ‘choosiness’ of young people irritates her the most. In one case of a successful female attorney from Houston, she also saw her mother as a stumbling block, giving out ‘negative vibes’ to prospective matches.

The first season features seven main characters, all in their thirties: four girls and three boys. There are a few minor characters with whom Sima aunty ‘matches’ them as potential partners. All the girls, barring one, are desis from the USA, with major ‘shortcomings’ that reduce the pool of matches available. The one with the fewest options, according to Sima, was Rupam, a divorcee with a child. Sima unabashedly says on camera, ‘anybody comes with a child, I usually do not take. Interestingly, Rupam appears to be a traditional Sikh girl who married within her community at the right age, but the failure of her marriage stigmatises her in the marriage industrial complex. To the delight of the spectators, she finds someone on Bumble before Sima can set up a date for her. The exchange between Sima and Rupam’s father reveals the nuances of the diasporic worldview. Sima proposes a match for Rupam with a divorcee. The father rejects the proposal because the man’s ex-wife is American. When Sima tries to argue that both Rupam and the boy were divorcees hence similar, he retorts ‘Rupam married a Sikh boy… who you are married to before that matters more than anything’. This statement provides a sneak peek into the diaspora’s attempts to guard community boundaries and resist inter-racial marriages.

Aparna Shewakramani is the quintessential Indian American who has been too busy pursuing her academic and professional goals, missing out on dating front. Aparna’s single mother-Jothika, is the one responsible for egging her on but after her ‘biological clock starts ticking’ is anxious for her to find the right partner. Taparia wants parents to ‘guide’ their children through the marriage process, but Aparna’s mother, who walked out of her own marriage, giving ‘negative vibes’ to the prospective match, does not really fit the bill for Taparia. Jothika is very clear she doesn’t want ‘someone to kill her daughter’s spirit’. Sima is visibly upset with Jothika when Srinivas Rao a prospective match visits Aparna’s house. Sima calls Aparna very stubborn, picky, negative, fickle minded, not stable …. She says, ‘When I think of Aparna, I get really tired … who can keep her happy? It’s a difficult thing.’

A battery of experts- astrologers, face readers, life coaches- are part of this marriage industrial complex with a long association with Sima Taparia. Janardhan Dhuree, a face reader in Mumbai who Sima consults always to assess the direction of her pursuits-appeared in A Suitable Girl as well- sees Aparna’s picture and confirms Sima’s opinion of Aparna. Dhuree certifies Aparna as stubborn and predicts that her husband will be subservient. He will tolerate her even if she slaps him’. Sima quips, this is what she wants’. This exchange reveals how women are perceived in the marriage industrial complex. Any assertion of choice or agency is intimidating and looked down upon. Aparna appears to be willing to do everything to find a match after two dates go wrong. An astrologer visits her, she wears a blue sapphire to ward off starry perils, invokes gods through mantras, and connects with her old friend, an astrologer of Korean origin based in India. Desperation is successfully built over five episodes, with Aparna disappearing thereafter, with Sima praying and leaving everything to destiny. Aparna is seen happy with Jay in a petting club doing yoga. On a video call later Sima tells her ‘I am finding a lot of changes in you.’ Aparna according to Sima remains stubborn but ‘open to her destiny’. In Episode 6, another successful entrepreneur from Delhi, a ‘head-strong’ girl Ankita Bansal, is introduced. She is very clear that her ‘partner needs to let her be the strong woman she is’. Sima makes it clear Ankita cannot fit in a traditional Indian family in India hence refers her to an associate matchmaker whose clients are less traditional. After one unsuccessful date with a divorcee who hid his first marriage, she decided to put a stop to the process and focus on her career.

Nadia Jageesar from New Jersey is an event planner who Sima finds ‘nice’ ‘easy going’ girl. However, her Guyanese origin becomes a roadblock with traditional boys. Nadia does Bollywood dancing which is highlighted as a subtle message to prove her Indian roots. While Nadia giggles at the drop of a hat and instantly connects with whoever she meets on Sima’s recommendations, finding love becomes a problem for her. She, in some senses, believes in the selfless love that she has seen between her parents. Her mother donated a kidney to her father without any doubts which to her was the epitome of selfless love.

Nadia first meets Guru, a boy with mixed parentage of Indian and Guyanese descent. For Sima, this was like hitting the jackpot, given her clientele. However, the date was unsuccessful. Nadia goes on a date with Vinay, and they click instantly. After meeting six or seven times which in Sima’s case was a positive experience, Vinay ghosts Nadia, leaving her heartbroken and Sima opinionated about Vinay being non-serious. Nadia now goes on a date with Sekhar, who had earlier rejected Aparna, who in turn was ‘positively undecided’ about him. Sekhar and Nadia are charmed by each other, and it seems to be working out. The face reader declares that they are aligned and will go on to have twins.

The boys in the first season were Vyasar Ganesan, a teacher from Austin, and Pradyuman Maloo and Akshay Jakhete, business scions from Mumbai. Vyasar belongs to a close-knit Indian diasporic family with a notoriously absent father. Sima is all praises for Vyasar and his good nature and sets him up with an ‘older’ girl which Vyasar doesn’t mind. They ‘click’ instantly, talking about issues like money and kids on their very first date. After a few online meetings, the girl rejects Vyasar. Sima thought that this was because of his low earnings.

Pradyuman Maloo from Mumbai comes across as the most eligible bachelor in the show. Rich, handsome Maloo is shown to have received over 150 marriage proposals, of which he is said to have met three or four girls. Pradyuman’s parents seem to have given up and tell Sima, ‘As a professional, if you talk to him, he will understand better’. Sima begins with collecting his preferences but as an aside comments ‘he will have to change his superficial nature’. His sister tells him, ‘You have to get out of this attraction bubble’. In every case, the boy or girl is made to feel guilty. Pradyumn agrees to meet a homely small-town girl, Snehal, whom he rejects. He is blamed for being self-obsessed and packed off to a life coach with expertise in understanding young people. Finally, Pradyumn meets Rushali Rai, a confident model who he likes, but the girl does not like him much which gets revealed in the next season.

The show opens with Akshay Jakhete’s mother displaying a bed box full of sarees and jewellery for his bride-to-be. However, he has no girl in mind to marry or even meet. His mother Preeti uses her BP monitoring machine as a blackmail tool to force Akshay to choose a girl. She even threatens to do it without his permission. Preeti has complete control over her family members. She manages her kitchen with a battery of helpers and a docile older daughter-in-law. She has a timeline for both her sons: the younger one has to get married within a year, and the older one has to bear a child the year after. Akshay, a Boston graduate driving around in a Mercedes, wanted ‘a girl like his mother’. The mother and son are very clear about what the girls place and role would be in their family. She has to adjust to the house rules of his mother. Preeti’s luncheons with her friends are dominated by the issue of Akshay’s marriage. Under immense pressure, he finally agrees to meet Radhika from Udaipur, to whom he gets engaged at the end of the season. Akshay and his mother invited a lot of wrath from netizens who minced no words in deriding them. A bulk of hate-watchers were unforgiving. Mundhra responded to criticisms of the cast upholding atavistic values by saying it ‘…spark(s) a lot of conversations that all of us need to be having in the South Asian community with our families – that it’ll be a jumping-off point for reflections about the things that we prioritize, and the things that we internalize.’

The second and third seasons saw new cast with new set of ‘issues’ besides reappearance of a few characters like Aparna Shewakarmi, Nadia Jageesar and Pradyuman Maloo. Aparna has moved cities trying to find love; Pradyuman found love on his ‘own’ and gets married; Nadia ‘destined to have twins with Sekhar’ falls for a ‘younger’ boy Vishal and ends her relationship with Sekhar. Sima aunty warns her about this being an unfeasible liaison but Nadia doesn’t listen. Nadia nurses a heartbreak after Vishal breaks up with her.

Akshay Dhumal, a rich businessman from Nashik, finds his small town a hindrance to his marriage. ‘Girls do not want to move to Nashik, ’ he says. Sima aunty just could not understand why? ‘Girls were marrying a city or the person’. She once again exposes her conservative side, whereby patrilocality is a given in marriage. One ‘choosy’ American Indian girl ends up falling for Aashay, a Gujarati boy born and brought up in India. Aashay had been recommended by Sima, and despite him not ticking important boxes in Viral’s preference list, he ends up with her.

Several other characters with roadblocks to marriage appear in seasons two and three. Some find partners on their own without searching Sima’s database. Interestingly, all of them credited Sima aunty and her process for ‘building momentum’, ‘being open about compromising’, and ‘seeing people differently’, which in turn helped them find partners. Sima advised one of the girls that while on date- ‘don’t think of the person as boyfriend, think (of him as) husband’. She repeatedly insists on ‘adjustment’ as she feels many of the things her clients list out as preferences are not important for a happy married life. She becomes visibly elated whenever a client shares the joyous news of finding a partner. However, she distinctly sets her approach apart from online dating platforms by emphasising a personal, human touch and trust along with accurate information.

Sima is a staunch believer in the idea of 'first marriage, then love,' a view shared by her colleagues, including a face reader and an astrologer, who see marriages as divinely ordained and predestined. She often says, 'matches are made in heaven, but God has given me the job to make them successful on earth.' Consequently, matching horoscopes has become a form of insurance for a successful marriage. At the start of the third season, Taparia acknowledges that her business has doubled. She is confident that the matchmaking profession will never end, despite its increasing challenges.

The idea for the show was first pitched a decade before it was streamed on Netflix. However, it was rejected due to the missing ‘white gaze’, as admitted by Smriti Mundhra. Indian Matchmaking’s appearance on Netflix in 2020 was humourous, authentically and unapologetically Indian, reflecting the perspectives of Indians, while also providing a nuanced understanding of the diaspora and illustrating its diversity. However, the show has been criticised for its ‘complicity in the normalisation of Hindu upper-caste culture as the larger Indian culture’ as it does not depict any Muslim, Christian, or Dalit characters.

The makers identified casting as the biggest challenge in putting the show together. The process of finding a girl or boy for marriage is very personal and is done behind closed doors. Doing it on camera was unimaginable for most of Sima’s clients, but a few agreed to bring this process into the light. They aimed to correct any preconceived ideas that some audience members might hold about relationships and matchmaking in South Asia. One of the participants, Guru Ravi Singh, publicly criticised the way his date was filmed and portrayed (Singh, 2020).

Indian Matchmaking, as a Netflix show, streamed simultaneously in India, US and many other countries. The glamour and glitz showcased through beautiful homes and large closets brimming with clothes and shoes, when viewed on smartphones and TV sets in modest homes, create new 'aspirational subjects' among millennials. Mankekar observes that 'regimes produced and circulated via television enable the creation of aspirational subjects in post-liberalisation India: these are subjects who aspire to become cosmopolitan regardless of their ability to acquire economic mobility' Mankekar (2012). The lives of the diaspora depicted on Indian Matchmaking—sipping wine, dating outdoors in Costco and Ikea showrooms, ice-skating, doing yoga or salsa—reinforce globalized market-driven regimes. The fact that people struggle to find partners despite having everything may be both cathartic and aspirational.

Indian Matchmaking fits well within the historical template of diasporic programming, relying on the tropes of nostalgia, heritage, and roots. Each episode opens with the banter of happily married Indian couples living in the US or the UK, with a few exceptions of resident Indians. Most couples recount their arranged marriages, emphasising the number of years they have spent together for a successful marriage. Sima Taparia frequently refers to her own thirty-six-year-old marriage, which she calls the 'golden period' of her life. All this helps to convince the doubtful viewer that, in the end, Indian arranged marriages are not bad.

While the show was criticised for normalising arranged marriages, it was also seen as giving a fairy tale account of a reality that is much worse. Many women found the show triggering, as it underscored how ambitious, intelligent, and successful women are often reduced to a set of clichéd descriptors in this marriage market, an experience that had scarred them for life. Although the producers of Indian Matchmaking saw hope in the possibility of generating conversations. Aparna Shewakarmi who was castigated as ‘difficult’ acknowledges that show itself had different standards for men and women. While she was categorised as stubborn after she rejected one match, men who had said no to 150 girls were only ‘unsure’. However, she also underlines the foregrounding of a collective feminine South Asian voice after the show brought attention to these issues.

The release of Indian Matchmaking during the Covid lockdowns helped its popularity in the US and India. It even found a spot on Netflix’s top ten charts and was nominated for the 73rd Emmy Awards in the Outstanding Unstructured Reality Program category. Indian Matchmaking received a mixed response, with many cringe-bingers and hate-watchers. It is an established fact that platforms capitalise on hatewatching as a profitable way to engage viewers and foster a lasting interest in their content Guha (2022). Bhandari (2020) points out that the anger may be because the ‘show has said it as it is, and has done so on a global platform, leaving little scope for pretence’’. The makers themselves underlined the need for authenticity: what’s real is real… we are not going to go out of our way to hide anything’.

5. Conclusion

The evolution of television in India, from state monopoly to the digital revolution, has significantly impacted the country’s societal values and cultural norms. The emergence of over-the-top (OTT) platforms has further transformed the media landscape, offering diverse content that balances tradition and modernity. Shows like Indian Matchmaking exemplify this blend, addressing traditional practices such as arranged marriages within a contemporary context.

Indian Matchmaking particularly highlights the persistence of traditional matchmaking practices in a globalised world, showcasing the complexities faced by both diaspora and resident Indians in navigating cultural expectations and personal desires. The show's popularity and subsequent seasons demonstrate a continued interest in exploring these themes while sparking important conversations about gender roles, family dynamics, and cultural identity.

The success of OTT platforms in India reflects changing viewer preferences and technological advancement. This shift has democratised content access, creating roaming audiences that consume media across various devices, particularly smartphones. This transformation has implications for identity formation, perceptions of national identity, and self-expression.

While OTT platforms offer more diverse and progressive content than traditional television, they still grapple with issues of representation and the normalisation of certain cultural narratives. The rapid growth and increasing influence of the industry underscore the need for continued analysis of its societal impact and the values it transmits.

As India's media landscape continues to evolve, it will be crucial to monitor how OTT platforms balance market demands with cultural sensitivity and how they contribute to shaping societal norms and values in an increasingly digital world.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bhandari, P. (2020, July 21). Matchmaking illustrates ills of Indian society. Hindustan Times.

Chang, P.-C., & Chiu, Y.-P. (2023). Factors influencing switching intention and customer retention of over-the-top (OTT) viewing behaviour in Taiwan: The push–pull–mooring model. Emerging Media, 1(2), 196–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/27523543231210140

Deori, M., Verma, M. K., & Kumar, V. (2021). Sentiment analysis of users' comments on Indian Hindi news channels using Mozdeh: An evaluation based on YouTube videos. Journal of Creative Communications, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/09732586211049232

Dutt, Y. (2020, August 1). Indian Matchmaking exposes the easy acceptance of caste. The Atlantic.

Eddy, W. C. (1945). Television: The eyes of tomorrow. Prentice Hall.

Fernandes, L. (2000). Nationalizing the global: Media images, cultural politics and the middle class in India. Media, Culture & Society, 22(5), 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344300022005005

Gomathi, S., & Christy, N. V. (2021). Viewers' perception towards OTT platform during pandemic. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts, 9(8), 593–693.

Jensen, R., & Oster, E. (2009). The power of TV: Cable television and women's status in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1057–1094. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1057

Johnson, K. (2001). Media and social change: The modernizing influences of television in rural India. Media, Culture & Society, 23(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344301023002002

Madnani, D., Fernandes, S., & Madnani, N. (2020). Analysing the impact of COVID-19 on over-the-top media platforms in India. International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications, 16, 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPCC-07-2020-0083

Mankekar, P. (2012). Television and embodiment: A speculative essay. South Asian History and Culture, 3(4), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2012.720077

Mehta, N. (2008). Television in India: Satellites, politics and cultural change. HarperCollins.

Mehta, N. (2015). Behind a billion screens: What television tells us about modern India. HarperCollins.

Menon, D. (2022). Purchase and continuation intentions of over-the-top (OTT) video streaming platform subscriptions: A uses and gratification theory perspective. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 5(1), 100006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teler.2022.100006

Menon, R. (2020, July 16). 'Indian Matchmaking' creator Smriti Mundhra puts a spotlight on the marriage industrial complex of the South Asian diaspora. Decider.

Mishra, N., Aithal, P. S., & Iyer, A. (2023). A study of the changing trends in the television industry. International Journal of Case Studies in Business, IT, and Education, 7(2), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.47992/IJCSBE.2581.6942.0276

National Readership Studies Council. (2006). The National Readership Study: Technical report. National Readership Studies Council.

Punathambekar, A., & Kumar, S. (Eds.). (2014). Television in South Asia. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315780979

Puthiyakath, H. H., & Goswami, M. P. (2021). Is over-the-top video platform the gamechanger over traditional TV channels in India? A niche analysis. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 31(1), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1326365X211009639

Raj, N. (2008, October 26). Saas Bahu and the end. The Times of India.

Rangaswamy, N., & Arora, P. (2015). The mobile internet in the wild and every day: Digital leisure in the slums of urban India. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(6), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877915576538

Singh, R. G. (2020, October 1). I was on Netflix's 'Indian Matchmaking.' Here's what you

did not see on the show. HuffPost.

Webster, J. G., & Lichty, L. (1991). Ratings analysis: Theory and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhShreejan 2025. All Rights Reserved.